The start

In Copenhagen 1958, researchers found out a “pox-like” disease in captive monkeys. Around the same time in 1959, the World Health Organization started a global campaign to eradicate small pox, a deadly disease which killed more than 300 million people since the 1900s alone. As the efforts for eradication of small pox started bearing results in most countries by 1970, scientists observed that a similar illness continued to circulate in the rural regions of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This disease was labelled “monkeypox”. Funnily enough, monkeys were not the major carriers of the virus and the virus persists in squirrels, rats, rodents or dormice instead. WHO then reported 54 cases of monkeypox between 1970 and 1979 and 338 cases between 1981 and 1986. That being said, monkeypox might have been infecting people for many centuries or even millennia because it was likely mistaken for smallpox since the two are clinically indistinguishable.

In 1980, WHO declared that we had eradicated small pox, after which people stopped taking regular vaccinations for protection against the virus. The next generation of children too remained unprotected from it. Due to this, about 70% of the population is now not vaccinated against the disease. Ironically, the aftermath of the eradication campaign has precisely been the reason for the rise in the number of monkeypox cases. The small-pox vaccines were found to have about 85% against monkeypox. Now that we have a mostly unprotected growing population, we are more susceptible to catching the virus. Theoretically, every time an outbreak would occur, it’s intensity too would dramatically increase.

According to a study published in February by US and German researchers, the number of monkeypox cases has increased at a minimum of tenfold and that in the Democratic Republic of Congo were suspected to peak at about 4600 in 2020.

The 2018 list of priority diseases for the WHO Research and Development Blueprint identified monkeypox as an emerging disease.

About monkeypox

Monkeypox virus is an Orthopoxvirus of zoonotic origins which is endemic to West and Central Africa. Its infection shares many clinical features of the small-pox virus except that it is less severe. Like small-pox, it has evolved into 2 distinct clades (or types) – Central African/Congo Basin Clade which has a mortality rate of about 10% (implying that 1 out of 10 people die) and the West African Clade which has a mortality rate less than 1%.

Primarily, the virus crosses over to humans by an animal bite, scratch, contact with the animal’s bodily fluid or through infected lesions (abnormal tissue growth). Then, it can be transmitted by contact and droplet exposure via exhaled large droplets – through coughing or sneezing or transfer of any other bodily fluids sexually amongst humans. Contact with live and dead animals through hunting and consumption of wild game or bush meat are also risk factors.

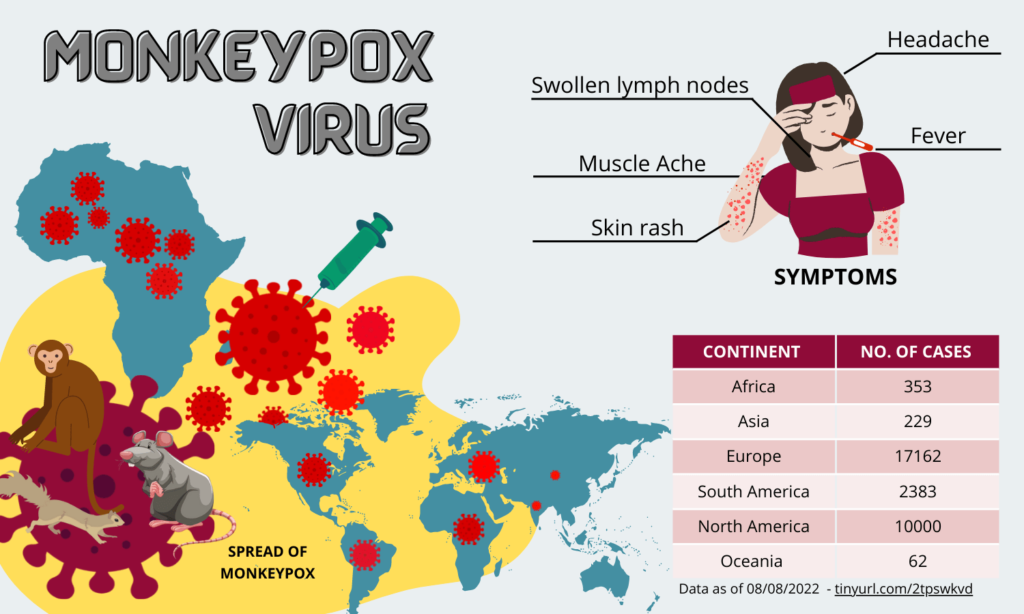

The incubation period of monkeypox may range from 5-21 days. Symptoms of monkeypox can include fever, headache, muscle ache, backache, swollen lymph nodes, rashes etc. Complications of the infections can include secondary infections, bronchopneumonia, sepsis, encephalitis and infections of the cornea with ensuing loss of vision. The symptoms often resolve on their own within a few weeks.

The 2022 Outbreak

On 7th May 2022, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) reported detection of a human case of monkeypox in a returning traveler from Nigeria. On 14th May 2022, two additional cases living in the same household in London and unrelated to the case reported on 7th May were confirmed with the virus. Neither of them had a travel history to West or Central Africa which was strange. Within the next 2 weeks, 15 more cases were reported and by the end of May, at least 21 other countries had reported confirmed cases.

“This outbreak is rare and unusual. Exactly where and how the people acquired their infections

remains under urgent investigation” was the statement given by the UKHSA.

The most bizarre part about this is the fact that most of the confirmed cases with travel history reported travel to countries in Europe and North America, rather than West or Central Africa where the monkeypox virus is endemic, which brings up the question – “Where did they contact the virus in the first place?”. This is the first time that many monkeypox cases have been reported simultaneously in non-endemic and endemic countries in widely disparate geographical areas. This is either suggestive of multiply exportations from an endemic region followed by unrecognized pattern of transmission or a single exportation to a non-endemic region after which a substantial transmission occurred. Either way, it is a cause for concern since we haven’t yet able to locate the

origin and trace its spread.

As of 29th July 2022, 20638 confirmed cases of monkeypox are reported out of which 20311 cases span across 71 countries that have not historically reported monkeypox. The US, Spain, Germany and UK have the leading number of monkeypox cases in the world. Most of the cases seem to have the less lethal West African Clade, however with the rate of mutation of the virus, we cannot predict as to the severity of the complications that will be caused.

This isn’t the first time a monkeypox outbreak has taken place

In 2003, 47 confirmed and probable cases were discovered outside the African continent for the first time in six states in the US. The outbreak was tied to pet prairie dogs which came in contact with mammals imported from Ghana in April earlier that year which carried the West African Clade of the virus.

Monkeypox has also been reported in travelers from Nigeria to Israel in September 2018, to the United Kingdom in September 2018, December 2019, May 2021, to Singapore in May 2019, and to the United States of America in July and November 2021.

In 2017, Nigeria began to experience its first outbreak in 40 years with a total of 183 confirmed cases

and 9 deaths between September 2017 and November 2019.

Why should we be concerned this time then?

One of the biggest reasons as to why we should be concerned is the sudden rise in the rate of transmission of the virus amongst people. For years, monkeypox outbreaks would almost die down instantly due to how poorly it spread in the community. The more time the virus spends inside people, the more time it has to evolve and currently the rising number of cases is a clear indication that the virus is rapidly evolving to transmit faster amongst humans. Thus, it is imperative that we safeguard ourselves from it.

Medical professionals suggest people take the following steps to help prevent the spread of monkeypox:

1. avoid intimate and skin-to-skin contact with a person who has a rash similar to that of monkeypox

2. try not to touch bedding, clothing, or other materials that may have touched a person with monkeypox

3. wash hands frequently with soap and water

4. in certain African regions, keep away from known animal carriers of monkeypox, and do not touch sick or dead animals.

An antiviral agent called tecovirimat – branded as TPOXX and made by SIGA Technologies – has U.S. and EU approval for smallpox, while its European approval also includes monkeypox and cowpox which could be a potential way to treat patients with the disease.

WHO has declared the outbreak to be a Public Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and it is absolutely necessary that the world doesn’t neglect the encroach of this virus onto it. Negligence has never proved to be beneficial for our society. Many scientists did not think SARS-CoV-2, would mutate to become more contagious, but that is exactly what has happened in the past two years and similar such examples like the Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks which were extremely deadly are prime examples as to why action needs to be taken on a global level.

The unpredictable nature of zoonotic viruses makes this outbreak especially lethal because we never know which direction it could take. With the world finally learning to cope with the shackles of COVID-19, we need to be extremely careful to prevent ourselves from entering in another global pandemic by doing our part and being aware and extra careful this time around.

References:

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/monkeypox-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-recent-outbreaks/

- https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5857192/pdf/mm6710a5.pdf

- https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2022/05/18/927043767/rare-monkeypox-outbreak-in-u-k-and-europe-what-is-it-and-should-we-worry

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2207323

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html#:~:text=After%20infection%2C%20there%20is%20an,beginning%20of%20the%20prodromal%20period.

- https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(18)34587-9/fulltext

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-history-of-monkeypox-180980301/

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/monkeypox-oubreak-2022

- https://www.reuters.com/article/health-monkeypox-concern-idAFL1N2Z60JR

. . .

Writer

Tanya Gadwal

Illustrator

Aishwarya G

Editor

Urja Kuber